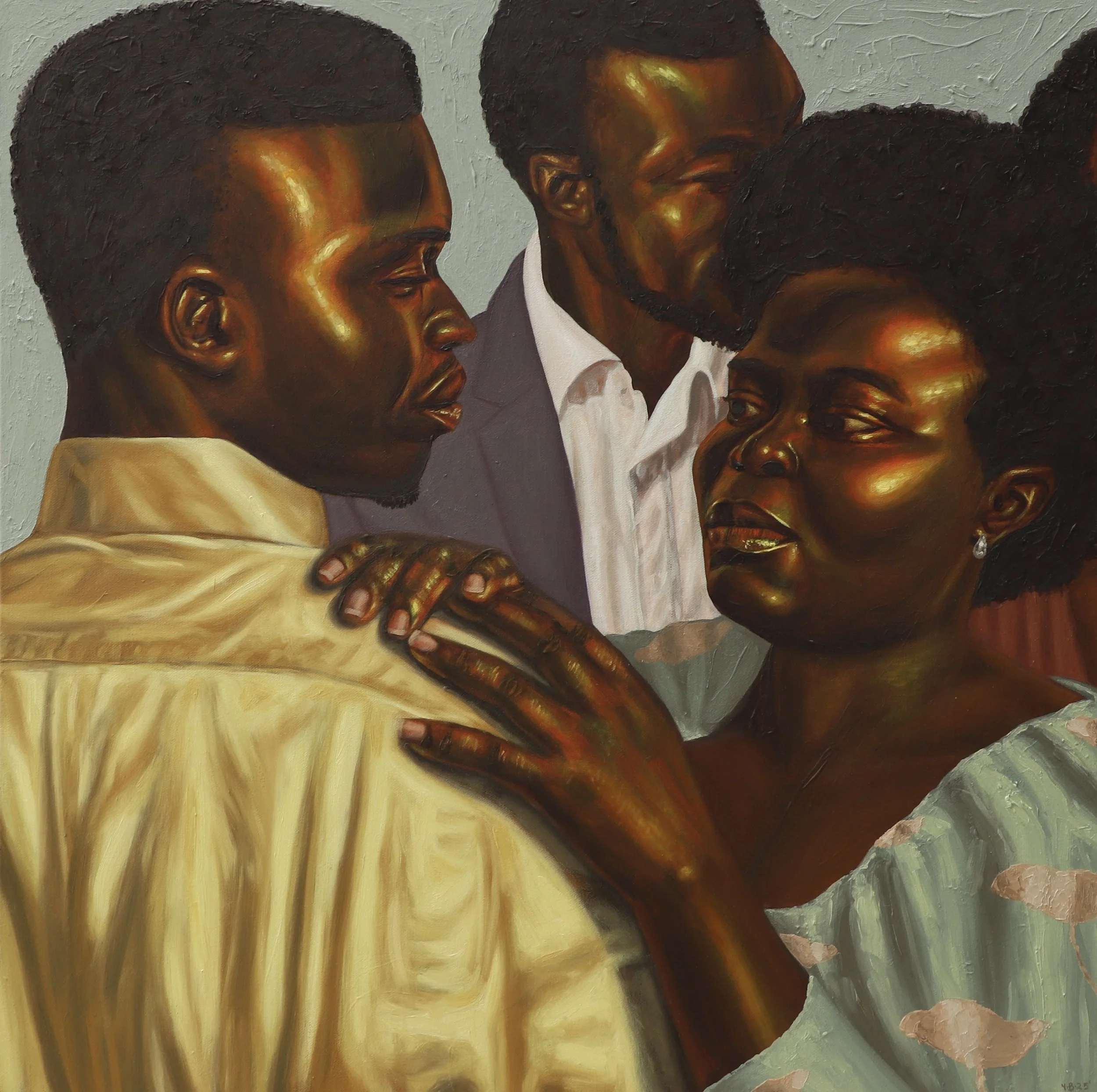

Barry Yusufu: The Weight of Worthiness

I spent the morning in conversation with Barry Yusufu, an artist whose portraits radiate quiet divinity and unflinching presence. Rooted in his Nigerian heritage and shaped by a profound sense of purpose, Yusufu paints everyday people; gardeners, sisters, friends, as embodiments of worthiness and grace. Now based in London and studying at Central Saint Martins, his practice continues to expand, probing questions of representation, belonging, and the afterlife of Black identity. Our conversation traced the spiritual weight of creation, the politics of visibility, and the evolving language of painting as both protest and prayer.

When I look at your portraits, there’s a quiet reverence in how each face is rendered, almost like prayer through paint. Do you view painting as a spiritual act, or is it something more instinctive for you?

Painting for me has always been a deeply spiritual act, because I come from a very spiritual African background. You know how it is growing up with a Christian mother in the house, that foundation shapes you. Those values have stayed with me, and I’ve always wanted them to reflect in my work and in the messages I share.

My figures embody everything that makes us human, the trials, the pain, the glory, all the things that truly matter. I try to express that through my imagery.

I’ve come to see art as a fine line between the physical and the spiritual. As artists, we receive divine ideas, and often we have no idea where they come from. They sit heavy in our hearts until we bring them to life. Only then are we set free.

Barry Yusufu, Behind you, Darling, 2025, Oil on Canvas, 24 × 24 inches.

Where do you get your inspiration from?

The ideas come to me in the middle of everyday life, like riding the tube and seeing someone ask for change. Moments like that drop a heavy message on me, something I feel I need to pass on. Once an idea comes, it sits with me. That’s the real beauty of being an artist.

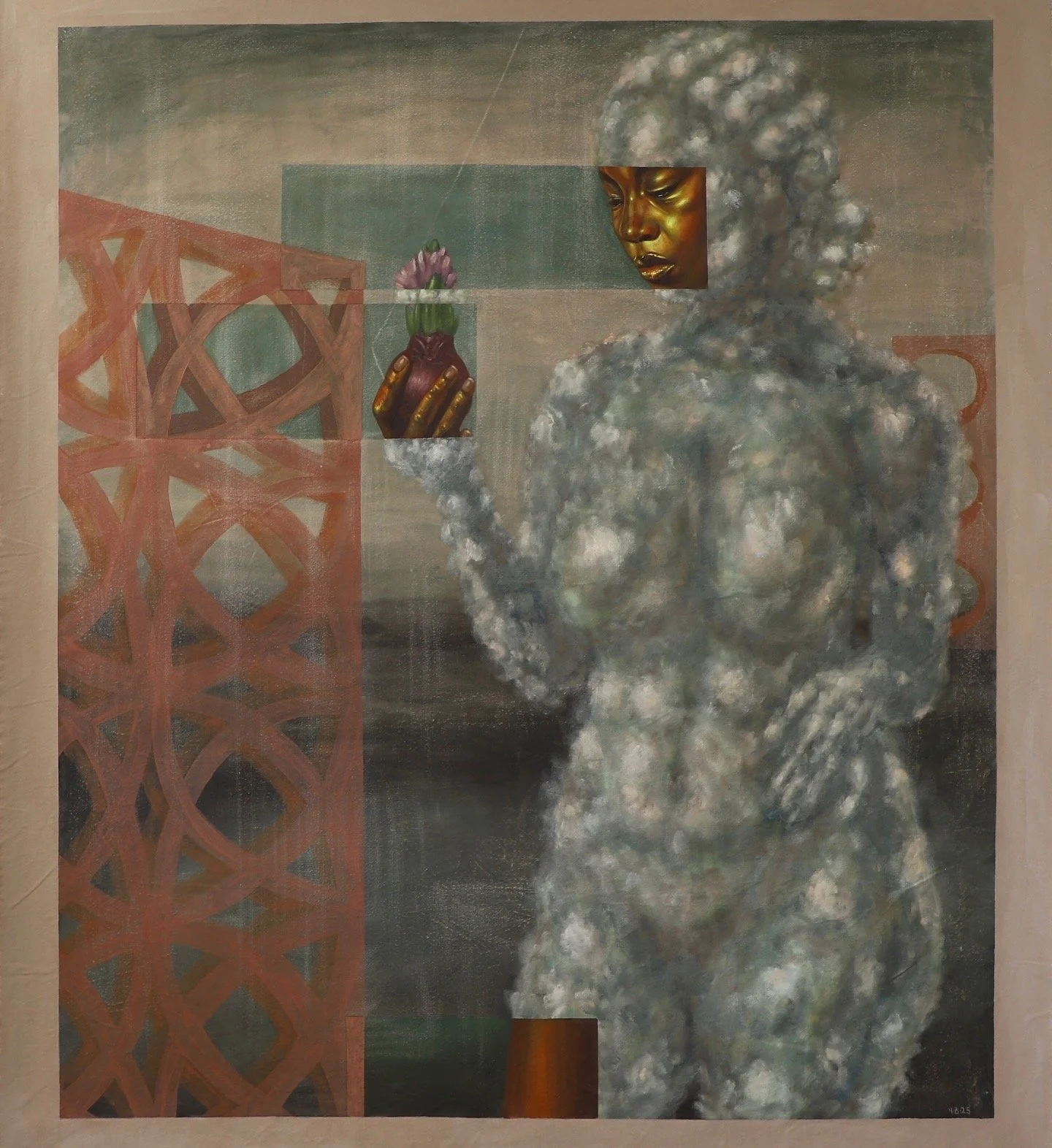

Barry Yusufu, An Old Line Tale, 2021, Oil on Canvas, 69 x 79 inches.

Do you start with exploratory sketches?

I almost never sketch. Some of the ideas I’m executing now, I’ve had them for over five years, but they’re buried somewhere...you keep pondering on them, returning to them. They keep haunting you. And it gets to a stage I call “the birth pain” and I feel I have to do this.

That’s why, for an artist, the profession feels like a calling. We’ve been chosen to do something that’s supposed to change the course of reality in a sense. So once that idea is ready, you eventually execute it.

You have a beautiful sense of intention and purpose. Would you say the process is more important than the execution itself?

That is where the real journey starts, when you execute that idea. That’s when the work can really achieve its purpose: to go into the world and pass on that message. Whether it’s to sensitize people, preach about love, make people understand what life is for certain kinds of people, or build the idea of community.

One particular piece may seem insignificant in the grand scheme of everything, but for every drop of water, there is that ripple effect. No matter how little it is, it matters.

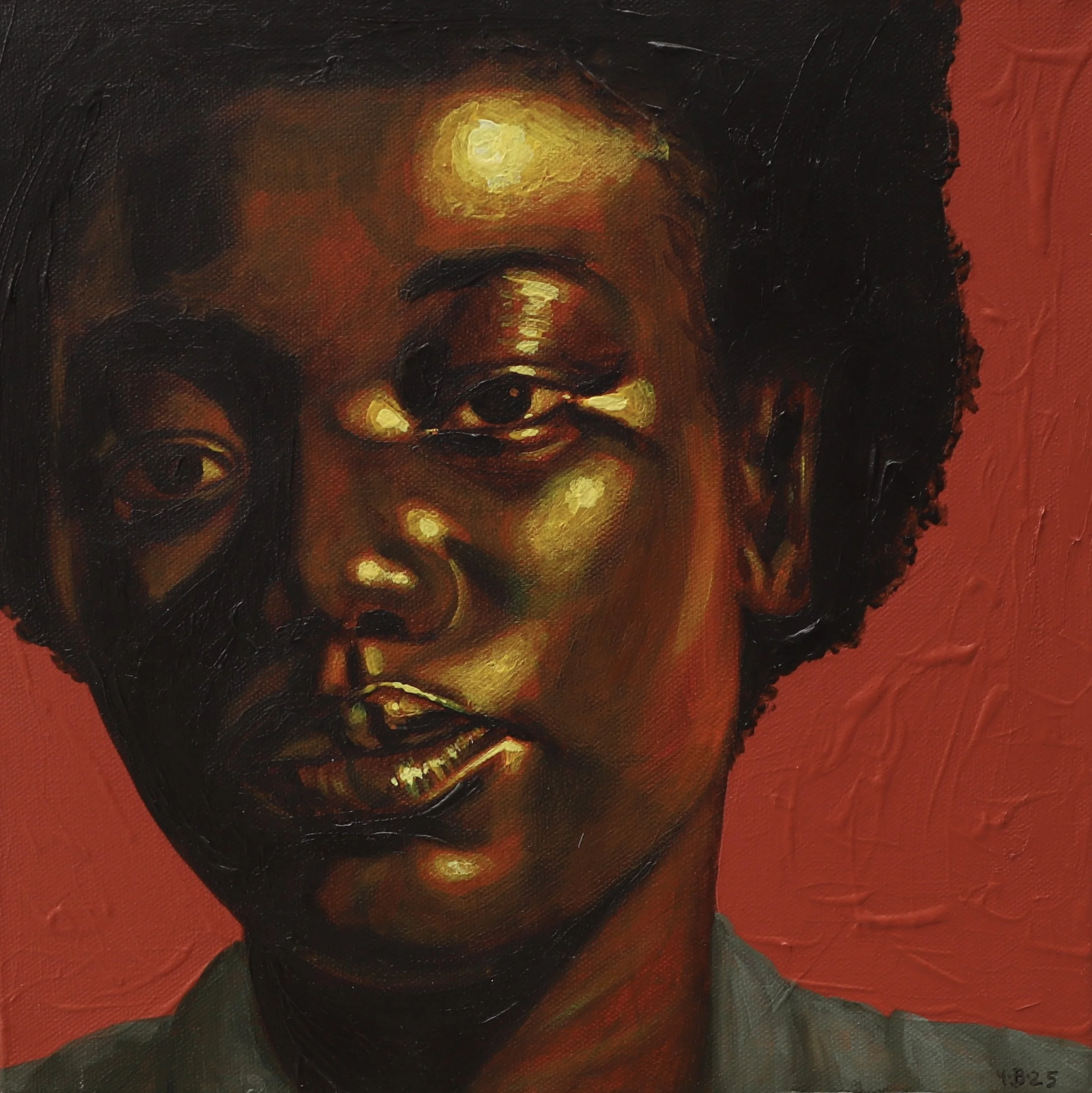

Barry Yusufu, Debayo, 2021, Oil on Canvas, 59 x 59 inches.

How do you know when it’s the right moment, when you get this “birth pain,” as you call it, that a piece has to come out into the world?

A typical example is when I did my first solo show. It was called Behold Sun’s People. Long before then, I had contemplated how best I wanted people, the black figures, to be seen.

I started off with charcoal and eventually added coffee into my work because at some point I lacked funds. Then I began dousing my charcoal figures in this heavy coffee, which created a new skin tone. Eventually, I was able to get paint and started adding acrylic into my work.

My work became stark black representation. That first body of work was about how Africans were seen as secondary to object, I wanted to put that in perspective. During that period, I had just yellow, orange, umber, and some white paints. I made experiments that created a kind of bronze, glossy idea, it felt like the best way to represent my people.

I remembered the Bible’s description of Christ: skin of bronze, hair white as wool, eyes like fire. That was the only description ever given of Christ. Yet, in religious spaces, all we see is a white figure. So I wanted to represent my people as worthy, divine, more than what the eyes can see.

How did the European galleries react to this vision?

Well, it was just bronze faces of regular African people. They told me it’s not marketable, that nobody wants to take the face of a giant Black person and put it on their walls.

Barry Yusufu, Anne, 2021, Oil on Canvas, 59 x 59 inches.

What a jarring statement. How did you respond?

I told these galleries that the world doesn’t know what it needs until you give it to them. And on the first preview of the show, all the works were sold out. It was an insane experience. It felt like a movement because nobody had seen that kind of representation before.

I felt I was doing what was right, painting my people the way I see them, and the way I believe they should be seen.

Barry Yusufu, To be here with you, 2025, Oil on Canvas, 30 x 30 inches.

Are you exploring similar themes in your current body of work?

I’ve had an idea for a long time where I wanted to paint what the afterlife of a Black person would look like. Africans are known to be the most spiritual people, yet they don’t see themselves as divine or worthy of salvation. Representation has been the greatest driver of the problems we face, racial, political, social.

For a typical Black person, we’ve never seen ourselves represented in divine spaces (Cathedrals/Bibles). So in this new body of work, painting the afterlife of Africans, I paint them as these cloud figures, spiritual, transcendent.

Where does the cloud reference stem from?

I took reference from the slaves who were shipped and made to pick cotton. Their spirits and souls were taken away from them, they were reduced to entities that only worked. Now I’m giving them their soul back.

Barry Yusufu, As Without, So Within, 2025, Oil and Acrylic on Canvas, 33 × 89 inches.

Many of your figures gaze directly at the viewer, it’s both intimate and confrontational. How do you approach the psychology of the gaze in your portraits?

If you don’t know where you’re coming from, you don’t know where you’re going. If I come from royalty, great wealth, and rich history, why should I settle for less now? Why shouldn’t I aspire to be great, creative, inventive? Africans are doing that every day. And in the eyes of the person you paint, you can see their entire story, and that story needs to be told.

This afterlife series is not just about our current reality, it’s about the future of the Black man.

Barry Yusufu, Till You Get Back 1, 2025, Acrylic on Canvas, 12 × 12 inches.

This idea of worthiness and divinity, the way you describe your portraits as godly, it’s profound. Does divinity exist in the person sitting for your work, in the act of painting, or in the final image itself?

My art is not just the final image. I paint divinity, the average person. Sometimes I walk up to people back in Nigeria: the laundry man, the gardener, my sisters, my friends.

That whole process, meeting these models, learning their stories, painting them, is what makes my art. Divinity lies mostly in the figure itself. I don’t think the artist creating is important, it’s the stories and the message that matter. I’m just a vessel.

Barry Yusufu, Don’t Worry, I’ll Fix It, 2025, Oil on Canvas, 30 x 30 inches.

Your works at the British Art Fair explored a slightly different theme. Can you expand on that?

The fair came at a time when the world feels colder and unfamiliar. We’re scared, unsure of tomorrow but we have to keep going. In this body of work, I’m painting memories and love, moments everyone can relate to.

A laugh with a friend, your hair being combed by your mother, a hug from your partner. Even if you don’t have love now, someone once cared for you. If we can remember what love feels like, it becomes easier to share it.

Barry Yusufu, Dearest Sister, 2025, Oil on Canvas, 24 × 24 inches.

How has studying at Central Saint Martins shaped the questions you’re asking in your work lately?

Being at Central Saint Martins has been wonderful. I’ve been influenced not just by the school but by my classmates. For the first time, I’ve painted in a shared space. Back in Nigeria, I always worked alone. Here, I interact daily with students, share contributions, that’s influenced my work.

But there’s always the question of Western influence. When I first painted the cloud figure alone, someone asked, “Is that Zeus?” That’s the issue, the moment a figure appears light, it’s assumed Western or mythological. I wasn’t painting anyone white; I was painting a figure made of clouds.

That reaction shows why the work matters. It opens a dialogue with Western art history.

Barry Yusufu, The Father and Sun, 2025, Acrylic on Canvas, 63 × 64 inches.

Do you see this same attitude within collectors?

People today are no longer interested in buying work just because a gallery says it’s important. People are buying culture, what they believe in. Galleries are confused, and that’s good. It removes what’s untrue and lets people decide what’s real.

There’s an interesting tension in your practice, you create work that challenges Western perceptions of Black identity, yet many of your collectors are white or Western. How do you reconcile that?

That’s exactly the point. Africa already understands African art. It’s the Western world that needs to see and engage with it.

When collectors hang my bronze portraits in their homes, their children grow up seeing them and start asking questions…why is this person painted in bronze, why in such an exalted way? That conversation matters.

Representation is everything. Showing Black people in their true, dignified form, that’s the message. No Black artist should feel their work doesn’t belong in these spaces. This is exactly where it should be.

You paint for your soul, but the world should benefit from it. Once your work gets out there and people connect, it begins to serve its purpose.

Barry Yusufu, Austin, 2021, Oil on Canvas, 49.5 x 49.4 inches.

I still see so much room for growth and change. The way you speak about these ideas is so important right now, your art carries activism, but in a way that’s poetic, personal, and relatable.

Thank you so much, Genevieve. I really appreciate it.