New York as Catalyst: Amela Rasi reflects on Residency Unlimited

Over the past several years, Munich-based artist Amela Rasi has developed a distinctive body of work that explores the tension between intimacy and distance, presence and absence. This year, she joined Residency Unlimited in New York, a program known for fostering research, dialogue, and exchange. Immersed in this new environment, Rasi has begun expanding her practice beyond her signature sewn canvases, experimenting with installation and sculptural forms. In this conversation, she reflects on the transformative energy of the residency, the importance of dialogue, and how stepping into a new rhythm has opened her work to new possibilities.

Before we dive into the residency itself, what drew you to it in the first place?

To answer that, I need to go back a little. For the last several years I’ve been based in Munich. I have three children, so I was very tied to home with my focus on my studio practice and of course on raising them. My daily life was really about discipline: carving out hours in the studio between family responsibilities, organizing time carefully just to finish my work.

It was a very concentrated way of working, but also quite isolated. I didn’t have much space to exchange ideas or see what was happening outside my immediate circle. Over the last year, as my children have grown a little older, I’ve felt things shifting. Suddenly there’s more space, more flexibility, and I realized this was the moment to step outside of that structure.

I also recognized a fear in myself, fear of becoming stuck in the routines of my practice, of repeating patterns without growing. That fear pushed me to look for opportunities where I could challenge myself and experience something new. The residency offered exactly that: the chance to step into a different rhythm, to immerse myself in exchange, and to open up to influences beyond what I could access in Munich.

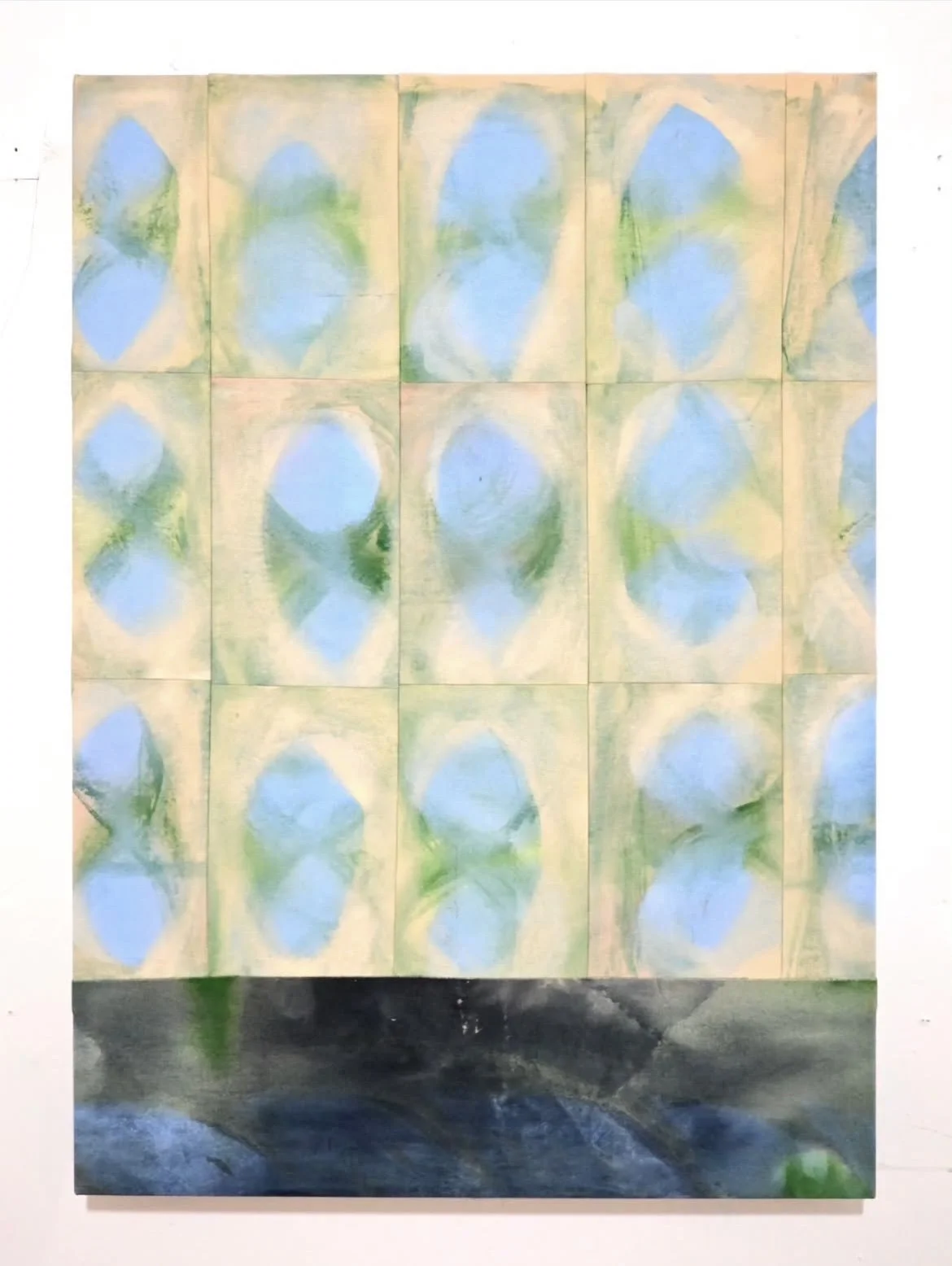

Amela Rasi, Forest Clearing, 2025, Pigment, Acrylic, Oil on cotton canvas, 94 × 61 cm.

© The artist, courtesy Galerie Amelie du Chalard

And how has it been so far?

Very inspiring. Residency Unlimited is quite unique compared to other programs I know. It isn’t focused only on producing new work in a studio. Instead, it emphasizes research, exchange, and dialogue. Each week we meet with other residents and with curators, gallerists, and art professionals. We present our projects, receive feedback, and enter into discussions that can take your thinking in unexpected directions.

Being in New York adds another dimension. The city itself is like a constant source of stimulation, so many exhibitions, so many artists, so much happening all at once. At first, it was overwhelming. Coming from Munich, where life is quieter and my days were very structured, the intensity of New York was almost too much. But once I adjusted, I realized how energizing it is. Every day offers the possibility of discovering something new. Even walking down the street becomes a kind of research.

What I value most, though, is the sense of community. In Munich, I often felt like I was working in a bubble…very inward, very focused. Here, there’s a constant exchange. Hearing how other artists approach their practice, how curators interpret your work, or even simply visiting exhibitions together creates a completely different energy. It’s been a big contrast to my more solitary rhythm at home.

Has this shifted your practice?

Absolutely. My work has always been about observing human connections, the tension between intimacy and distance, closeness and separation. Recently, I’ve started exploring how those dynamics are shaped in the digital age, where presence and absence blur in new ways.

During the residency, I felt encouraged to experiment beyond my usual format of sewn canvases. I began testing ideas for installations and sculptural pieces. For me, that was a big step, because my practice has always revolved around fabric and the act of sewing. To translate those ideas into three-dimensional space is challenging but also exciting. It opens possibilities I hadn’t fully considered before.

Can you walk me through your process?

It often starts with research. I read, collect references, and observe. I write notes, sketch, and test ideas on paper. From there, I begin to translate concepts into material form, usually with fabric.

Sewing has always been central to my practice. I cut, layer, and stitch pieces together to form compositions that hang like paintings but often feel sculptural. The act of stitching is significant, it’s a physical process, but also metaphorical. What I love is that the process is very bodily. It requires movement, repetition, sometimes even endurance. That physicality keeps me grounded in the material, even when the ideas I’m exploring are abstract or conceptual.

Amela Rasi, Rescue Boat, 2025, Pigment, Acrylic, Oil on cotton canvas, 94 × 71 cm.

© The artist, courtesy Galerie Amelie du Chalard

Can you expand upon the concept of these new works specifically, Rescue Boat and Forest Clearing?

While creating the works I've been dealing with the definition and idea of 'shelter'. My exploration of 'shelter' examines the ambivalence of a fundamental human need: protection as safety, yet at the same time a fragile balance between security and threat.

The work 'Rescue Boat' reflects the ongoing migration across the Mediterranean. The lifeboat, traditionally a symbol of survival, loses its protective function in the moment of use and turns into its opposite. The nine unevenly weighted figures point to a disturbed balance and mark the beginning of a series that can never capture the true extent of this movement.

'Forest Clearing' addresses Shelter as an inner, mental space. Beneath an overwhelming night sky lies a dense forest with small clearings that appear as islands of refuge, metaphors for individual quests for meaning and for the search for inner safety.

Do you consider your work closer to painting or to sculpture?

It’s somewhere in between. My pieces hang on the wall and carry the presence of paintings, but the sewn layers and textures give them a sculptural quality. I like that tension, they don’t fit neatly into one category. Moving into installation and three-dimensional work during this residency feels like a natural extension of that in-betweenness.

Amela Rasi, Sun, 2025, Clay, Glaze, Oil colors, 30 × 25 cm.

© The artist, courtesy Galerie Amelie du Chalard

Was there a specific conversation from your time at the residency that struck you?

Yes, I actually felt a bit insecure about how to lead the conversation about my new body of work. I spoke to a companion and told her about the new direction I’d like to explore. She immediately connected it to a sculpture she had in mind, one that’s exhibited at the Met Museum. She suggested I go and see it, saying it could be really helpful for the installation I’m thinking about.

So that’s what I did. I went to the Met, wandered through this huge museum, and eventually found the piece. Seeing it made such a difference. It helped me start sketching my own ideas before that, I wasn’t sure how to even begin with the sculpture.

Mangaaka Power Figure (Nkisi N’Kondi), Yombe-Kongo artist and nganga (ritual specialist), ca. 1880–1900, Republic of the Congo or Cabinda, Angola, Chiloango River, Wood, iron, resin, ceramic, plant fiber, textile, pigment.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 344.

What was it about that sculpture that opened things up for you?

It was a power figure. These figures, used in different tribes in Africa, are connected to ceremonies led by priests. They’re believed to protect against problems or bad spirits. Needles carrying these spirits are stuck into a specific section of the figure, only one part of the sculpture is designated for this. That’s just a small part of the story of the power figure, but it struck me.

I started thinking about how to translate that idea into something connected to our present. Today, when we have a problem or seek answers, we turn to our own kind of power figure: the phone, and by extension, the internet. For years it was Google, now it might be ChatGPT or another AI program. The phone has become the object we consult, the thing we put our faith in.

But of course, the phone isn’t a particularly beautiful or sculptural object. I wasn’t sure how to reimagine it as a power figure. That’s why her suggestion was so valuable. It didn’t take many words or unnecessary explanation, she simply offered the right reference at the right time. That kind of exchange shows the quality of a good conversation: she was really listening, and she knew exactly where her experience and knowledge could guide me.

Speaking of inspiration, which artists or exhibitions have influenced you recently?

In New York, several exhibitions have left a lasting impression on me. At Hauser & Wirth, Ambera Wellman’s paintings opened up a surreal world that felt as tangible and immediate as the reality we live in. At David Zwirner, Andra Ursuța’s cast-glass sculptures fascinated me, the transformation of such a fragile material into what looked like precious fossil discoveries from another world, and the way they were presented, was deeply moving. Florian Krewer’s paintings at Michael Werner Gallery struck me with their incredible mastery of color, I loved the balance between dense, impasto surfaces and areas of smooth, fluid paint. And at Post Times, Richard McGuire’s small drawings revealed intimate worlds and quiet details without ever feeling intrusive.

There were, of course, many more exhibitions that offered something special, it’s impossible to name them all. But in general, I feel a strong connection to the work of Sterling Ruby, Rosemary Mayer, Eva Hesse, Rosemarie Trockel, Joseph Beuys, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Their approaches to material, form, and presence continue to resonate deeply with me.

Ambera Wellmann, People Loved and Unloved, 2025, Oil on linen; diptych, 213.4 x 365.8 cm

© Ambera Wellmann Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer

Do you feel those influences directly entering your practice?

Not directly, but in the sense of permission. Seeing how these artists take risks, experiment with materials, or embrace scale gives me courage. It reminds me that it’s possible to stretch the boundaries of your practice without losing its essence. I’ve always been drawn to monochrome, black and white work. I used to find colour distracting; it made the process too intellectual instead of instinctive. So I kept my palette simple, and I was never bored.

Balancing three children and a career can be a huge challenge. Do you feel like this residency marks a new chapter for you?

Yes, very much so. For years, my practice was shaped by necessity, working within strict boundaries of time, often alone, always balancing family and studio. That discipline was important, but it also limited me.

The residency gave me the chance to step out of that daily structure. To immerse myself in an environment where exchange and discovery are at the center. That shift feels transformative. It’s not only about what I’m making now, but about how I imagine the future of my work.

I don’t yet know exactly where it will lead, but I feel re-energized. Less afraid of getting stuck, more open to change, and more confident that my practice can continue to grow even as I balance different roles.